Pandemics and Hunger: Lessons from the 1918 Pandemic in India

It wasn’t the influenza virus alone, but the agricultural exploitation imposed by colonialism which devastated India in 1918.

A patient treatment and isolation ward in Bombay. Image: Narratives of the Bombay Plague via Outlook

As government-imposed lockdowns against the COVID-19 global pandemic have brought much of the world to a stand-still, the question of food has assumed central importance. This is often framed in terms of food provision as an essential service which is being disrupted by restrictions at various stages of the commodity chain. That is, a question of maintaining transportation of food commodities while limiting the movement of consumers and labour. However, such an analysis ignores that there was already a food crisis for many prior to the pandemic. It also leaves unquestioned the role of capitalism in producing populations vulnerable to global crises.

The national lockdown in India is causing concern over an impending food crisis, as transportation networks and labour supply are impacted. Similarly, working peoples in Pakistan are experiencing the strain of increased prices of food staples like rice, sugar, and pulses. This is despite a drop in international prices of diesel, pulses, edible oils, and tea. Lockdowns in Pakistan are similarly interrupting the transportation of food commodities. As the wheat harvest is upon us, there is a labour shortage as landless workers stay home while others feel empowered to demand higher day wages from landlords.

While there is reason to be concerned about the impending food crisis, we also need to ask: for whom will there be a crisis? More importantly, what do we mean by a food crisis?

One could argue that a food crisis was already underway prior to the novel coronavirus arriving in the subcontinent. The 2018 Pakistan National Nutrition Survey found that 36.9% of the population experiences food insecurity, probably an underestimate in itself. The Food and Agriculture Organization reports that 14.5% and 20.3% of the population is undernourished in India and Pakistan, respectively.

Food insecurity is of special concern at the present moment — malnutrition leading to a weak immune system profoundly increases the rate of mortality from a viral infection. These effects were clearly observed during the influenza pandemic of 1918-19, which killed 50-100 million people worldwide. While public health experts today emphasize individual choices in good hygiene practices – thorough handwashing, physical distancing, eating well — the key lesson to take from 1918 was that mortality had much to do with historical and social processes beyond the impact of personal effort.

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic

While the 1918 influenza pandemic was a global phenomenon, its death toll was highly uneven. When the first cases of the virus were observed in Europe, it was still the site of World War I. Trenches across Europe proved to be especially lethal spaces as military personnel were in close proximity to each other. While approximately 2.3 million people died in Europe, the disease was especially deadly in British India, causing a staggering 18.5 million deaths. What explains this unevenness?

“While approximately 2.3 million people died in Europe, the 1918 pandemic caused a staggering 18.5 million deaths in British India.”

The first cases of the H1N1 influenza virus in the Indian subcontinent were observed in Bombay in June 1919. It was brought there by British Indian Army soldiers returning from the Western Front of World War I.

From Bombay, the virus spread across the subcontinent that summer via British Indian Army personnel. Yet, it was only in a mutated form spread in a subsequent wave in October that the virus became especially lethal. Again, it spread across the subcontinent starting from Bombay.

Mortality by Race/Caste: Influenza and all causes, Bombay City, 1918 (Mortality/1,000 population). Source: The Conversation

In Bombay, the influenza pathogen was transmitted across the general population – from the British to Indians, upper to lower caste Hindus. However, its mortality rate was starkly differentiated. The mortality rate in upper caste Hindus and Muslims was more than double the rate of Europeans in Bombay. Even more shocking was that lower caste Hindus had over seven times higher mortality rates compared to Europeans.

What explains this differentiated mortality?

“the pandemic combined with a historic famine in India produced “mutually exacerbating catastrophes”

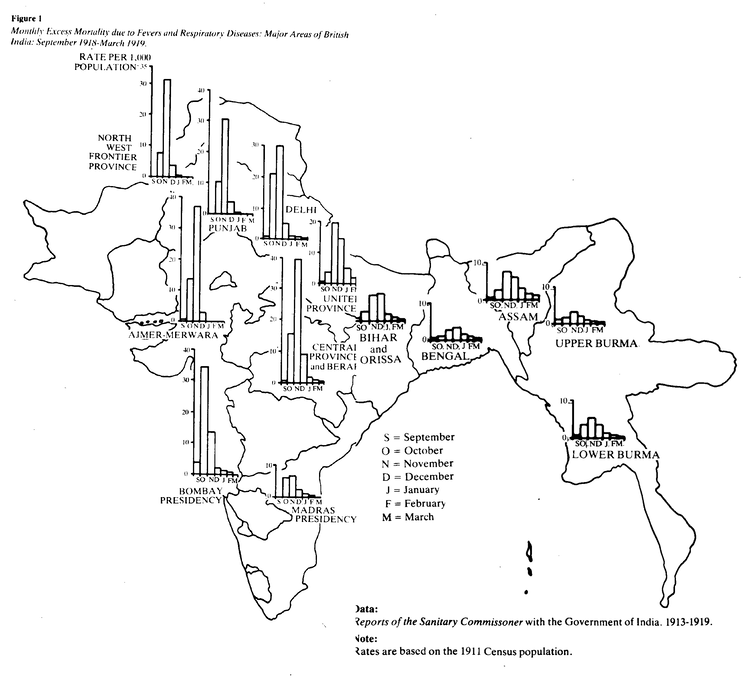

In his seminal article, the historian Ian Mills has argued that the pandemic combined with a historic famine in India produced “mutually exacerbating catastrophes”. During the summer of 1918, an unusual reduction in monsoon rainfall caused significant crop failures. It affected broad swathes of India, including Punjab, Gujarat, Bombay, Deccan, Behar, Rajputana, the southern part of Central Provinces, Orissa, and United Provinces. This corresponds with zones that were also the most affected by the influenza virus. Crop failures led to widespread food insecurity, which caused malnutrition and a weakened immune system that was increasingly vulnerable to infection.

However, the failure of the monsoon is not the only factor responsible for influenza’s devastating impact on India. Mike Davis has argued that droughts don’t just inevitably lead to disasters — there are social and historical processes that facilitate that jump. In the case of India, the colonial state’s transformations of the food system for decades prior to the influenza outbreak were integral in turning the monsoon failure into a crisis.

Monthly excess mortality due to fevers and respiratory diseases across all provinces of India: September 1918 - March 1919. Source: I. D. Mills in The 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic - The Indian Experience.

Food Insecurity and Agrarian Transformation in Punjab

Take the case of Punjab, which experienced an estimated 962,937 influenza-related deaths in just three months, from October to December, according to a colonial government report. When the mortal strain of the virus came to Punjab via military personnel in cantonments, it quickly spread to nearby towns, villages, and markets. Though there is a dearth of records on the impact of the pandemic in Punjab, this government report described the gravity of the situation:

The hospitals were choked so that it was impossible to remove the dead quickly enough to make room for the dying: the streets and lanes of the cities were littered with dead and dying people; the postal and telegraph services were completely disorganised; the train service continued, but at all the principal stations dead and dying people were being removed from the trains; the burning ghats and burial grounds were literally swamped with corpses, whilst an even greater number awaited removal; the depleted medical service, itself sorely stricken by the epidemic, was incapable of dealing with, more than a minute fraction of the sickness requiring attention; nearly every household was lamenting a death, and everywhere terror and confusion reigned.

In contrast with the 5% mortality rate of Europeans and upper and middle class natives in Punjab, the lower classes faced a staggering mortality rate of up to 50%. Young and middle-age adults, especially women, experienced higher rates of death. Rural areas were also more affected then urban areas. Colonial administrators conveniently laid blame on differential access to quality medical attention and unhygienic conditions, especially in the countryside. The colonial administration stated:

In the present epidemic the poor and the rural classes were adversely affected by the economic conditions resulting from the war and the failure of the monsoon. Food prices were high, a sufficiency of blankets and warm clothing almost impossible to obtain, and milk was scarce owing to the fodder famine.

Such reports make it appear that the dramatic mortality rates in India resulted simply from a confluence of contingencies (monsoon failure, the war) — natural or historical events which could not have been controlled. They also effectively blame the poor for their poverty and for living in unhygienic conditions.

But these contingent factors, though important, fail to explain why landless agrarian workers are less able to access hygienic conditions and quality medical care. And it ignores the social and historical processes which created the conditions for malnutrition ripe for the mortal influenza strain. To understand this, we need to examine the colonial transformation of the agrarian system in Punjab.

Punjab was forcibly occupied by the British in the late 1840s. At this point eastern Punjab (in contemporary India) relied on rain-fed agriculture, whereas western and central Punjab (shared between contemporary Pakistan and India) was mostly dominated by nomadic pastoralism and some agriculture near rivers and wells. Agriculture was governed by a system of land rent payments to the government as a portion of the harvest.

British colonization made several changes to this system. It introduced private property and formalized land tenure, such that it assigned selective castes and kin groups with land, while making whole sections of the population sharecropper tenants and effectively landless. Payments to the state were to be made as fixed cash amounts, which led many to incur debts with moneylenders. Western and central parts of Punjab that were previously dominated by pastoralists were slowly made into agricultural fields through massive projects of canal irrigation.

This new agrarian frontier had the explicit purpose of extracting greater degrees of rent from the population for the colonial purse, but these developments were also simultaneous with the integration of Punjab in an international food market. Roads, railways, market towns, the port of Karachi, shipping lanes, and opening of the Suez Canal all came together to create the conditions for this integration. Where food was previously produced for personal consumption or local markets, fields were quickly transformed to produce cash crops, like wheat, for the export market.

“The famine of 1878-79 killed about 1.2 million people in Punjab. Yet, export trade [of agricultural products] continued apace.”

While those who were given large landholdings benefited from this new order, the vast majority of small peasants, tenants, and other landless peoples were crushed under debt, disease, and famine. Droughts increasingly turned into famines during British rule because precolonial famine relief systems were dismantled and new measures were underfunded. The colonial state’s policy was to not intervene during moments of grain scarcity. The famine of 1878-79 killed about 1.2 million people in Punjab. Yet, export trade continued apace. This was not because agricultural producers in India chose to produce and sell cash crops for the international market. Rather, there was a significant dimension of violence involved: British-imposed fiscal policies and requirement to pay land revenue in money made cash crops for export the only viable option in the new political economy.

Indian peasants were effectively subsidizing British industrialization. While the peasants of the subcontinent were going hungry, British workers benefited from the situation. During the Great Depression of 1873-1896, Britain saw a drop in food prices and thus real wages rose significantly. While there was a reduction in employment, this was not enough to affect the overall gains made by workers as a class. In India, as rising food prices were not matched by rising wages, the standard of living dropped.

A periodical of the Ghadar Party from 1914 circulated information on national mortality due to famines and plagues. Point (4) reads: “Famines in the British Raj continue to increase, over 2 crore people have died due to famines in the past decade alone”. Point (5) reads: “80 Lakh people have died due to various plagues over the past 14 years. There has been an increase of 24-34,000 deaths in the past 3 years alone.” Source: Ghadar (Urdu) Vol. 1, No. 22, March 24, 1914.

The influenza pathogen did not induce a food crisis in 1918. Rather, food insecurity was already a significant problem in the region. Radical anti-colonial movements of that period, like the Ghadar Party in Punjab, understood this. They articulated in their pamphlets in the early 1910s how famines were not the products of nature (e.g. drought) or overpopulation — rather, they highlighted how an imperialist food system produced social and spatial unevenness. It was uneven in terms of who produced food, who controlled the conditions of that production, and ultimately who received the surplus of production. When there were widespread anti-colonial protests the year after the deadliest period of the influenza pandemic, in the spring of 1919, they were spurred by a reaction among the native population against multiple grievances, including the colonial government’s response to the pandemic and the high body count. It is an open question whether this present moment will provide the context of similar mobilizations.

Fast Forward to COVID-19

This sojourn to the colonial period highlights the centrality of food and nutrition in building strategies for the current pandemic. Indeed, relief programs of multiple governments in South Asia are taking food into account. The government of Pakistan issued a $7 billion relief package, which includes $1.6 billion for wheat procurement and $300 million to support utility stores. The government of India announced that it will provide 5 kg of rice or wheat and 1 kg of pulses per person each month for free. These strategies are in line with the World Bank’s recent report on South Asia that finds economic instability on the horizon due, in part, to an impending food supply disruption crisis. While they recognize that the present crisis will deepen inequality such that the poor will be most affected, they fail to address the social, historical, and spatial processes that make a large section of the population vulnerable to a pandemic in the first place.

“The sad contradiction is that the majority of rural workers don’t have enough to feed themselves.”

The key lesson from the high mortality rates caused by the 1918 pandemic is that it wasn’t the virus itself that killed millions in South Asia. Rather, British colonialism created the context for the pathogen to leave so many dead. Similarly, hunger in South Asia is not a problem that begins with COVID-19. To address food insecurity, we need to look at the historical and ongoing processes that make hunger.

Widespread malnutrition is the product of landlessness that has its roots in colonial-era land assignment. The sad contradiction is that the majority of rural workers don’t have enough to feed themselves. This is not due to a lack of land productivity or overpopulation, but a result of the sharecropping system which makes subsistence impossible. Many smallholders lost land with the introduction of the Green Revolution as they were unable to compete with large landholders who had the capital to introduce such technologies. Transnational corporations increasingly exercise greater control on the food system in the subcontinent and beyond. They have also shown interest in addressing malnutrition through “food fortification” – food processing that increases select nutrients. This may sound like a good idea, but in fact such a move fails to historicize malnutrition. Rather, food fortification is only a mechanism for greater corporate control of food production.

Migrant laborers in Amritsar protest against the lack of food banks after the Indian government extended the national lockdown without announcing any relief measures - April 22, 2020. Source: Narinder Nanu / AFP via The Nation

While many praise Chinese foreign direct investment in Pakistan, such developments in logistics serve to take surplus production out of the country thus taking further control away from small-scale peasants and landless labour. We are also witnessing increasing Chinese land grabbing across the country. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is not unlike British investment in railways, roads, and ports in the late 19th and early 20th century. As lockdowns in India and Pakistan disrupt food supply provisioning and cause concern over food access, we need to ask whether the pre-existing infrastructure and logistics of food were intended for those most hungry after all.

The World Health Organization has said the worst of the pandemic is still to come for the Third World. The uncertainty of the future should not prevent us from limiting our understanding of the food crisis beyond the immediate timeframe of COVID-19. The pandemic of 1918 and the one today demonstrate how capitalism is unable to maintain life for everyone. Any strategy out of this crisis must understand the problem of food access in South Asia in the framework of capitalist relations, which are mediated by sharecropper-landlord relations, transnational corporate control over food production, unequal bilateral and multilateral trade agreements, and government interventions that favour large landowners and foreign corporations.

As the spatial and social unevenness of capitalism produces differentiated vulnerability along the lines of class, gender, and caste, any strategy to address food insecurity and malnutrition must be oriented towards landless labour and small-scale peasants, especially women, reclaiming greater sovereignty over the production and distribution of food. As such, pro-poor land redistribution must be an integral part of this strategy. Agro-ecological food production provides a pathway for reclaiming peasant sovereignty over food, land, and labour from transnational, foreign, and local capital. This will require people to re-imagine how society should be organized at the local, national, and international scales.

Kasim Tirmizey has a Ph.D. in Environmental Studies from York University in Canada. He has taught in universities in Canada and Pakistan. His research is on the politics of food in Pakistan.