Indo-Soviet Cinema and Socialist Internationalism

For Indian and Soviet filmmakers of the 1950s and 1960s, cinema emerged as a site to forge a hopeful, if tenuous, ethos of socialist internationalism.

“Soviets and Indians are Brothers”: Soviet Union propaganda poster.

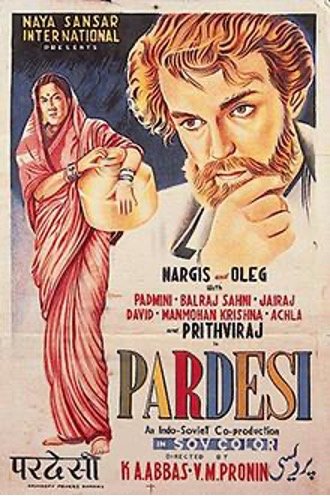

The first ever Indo-Soviet coproduced film was K.A. Abbas and Vasili Pronin’s Pardesi (1957), a dramatization of the fifteenth-century Russian traveler Afanasy Nikitin’s voyage to India. In the final scene, Sakharam, a philosophically-minded folk-singer who lives in India, bids farewell to his departing friend Afanasy, singing “phir milenge jaane waale yaar, do svidanya” (“We’ll meet again, friend, we’ll meet again,” rendered lyrically in both Hindustani and Russian). The camera cuts between the ebullient Sakharam, with his frame drum and musical troupe among a crowd on the shore, and the grave Afanasy, standing on the ship with his hand over his heart. As Afanasy sails away, the chorus of voices ascends frenetically, singing a prolonged and repeated “do svidanya” set to a triumphant orchestral arrangement before a final fade to black, implying that “we” — India and the Soviet Union — will indeed meet again.

“For Indian filmmakers of the 1950s and 1960s, the Soviet Union was a crucial touchstone, informing the aesthetics, craft and progressive messaging of their films. ”

Pardesi’s closing moments evoke a time of Indo-Soviet camaraderie in the aftermath of Indian independence and in the context of the Thaw, when warm diplomatic relations between Jawaharlal Nehru and Nikita Khrushchev facilitated cross-cultural exchange and political solidarity. In the world of cinema, Indian and Soviet filmmakers, producers, actors, and screenwriters were inspired by each other, with delegations, workshops, and film festivals of one country being organized in the other. For Indian filmmakers of the 1950s and 1960s, the Soviet Union was a crucial touchstone, informing the aesthetics, craft and progressive messaging of their films. These early Indo-Soviet cinematic encounters did not just reflect a radically internationalist, if short-lived, socialist paradigm — they also helped produce it.

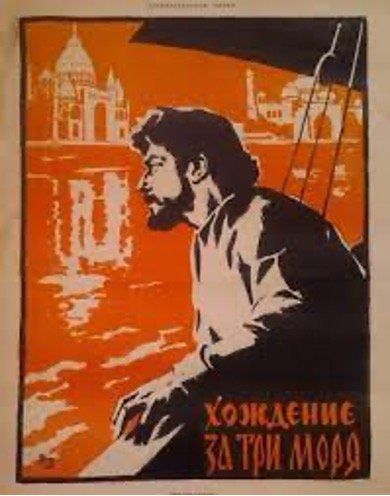

The Indian and Soviet posters of Pardesi. Image: IMDB

Indo-Soviet Encounters: A Brief History

During the final years of Stalin’s regime, Soviet attitudes towards India were marked by indifference, especially as the newly independent country decided to maintain cordial ties with the West and refused to embrace communism. But Khrushchev’s Thaw transformed Indo-Soviet relations. Under Khrushchev’s new foreign policy of “peaceful co-existence,” the Soviet Union now sought to cooperate with recently decolonized Asia and Africa. Earlier dismissed as a national bourgeois state, India was reconstituted as an important socialist ally, with Nehru — who admired the Russian Revolution and Soviet-style central planning — at its helm.

During their 1955 visit to India, Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin emphasized this solidarity, underscoring the Soviet Union’s admiration for both India’s anti-colonial struggle as well as the country’s role in creating a favorable balance of power. In his first speech, given immediately upon landing at the New Delhi Airport, where he was welcomed by tens of thousands and garlanded with flowers, Bulganin declared:

The heroic struggle of the freedom-loving Indian people to restore the independence of their homeland has always met with understanding and warm sympathy from the peoples of the Soviet Union…Our people have a profound belief in the creative forces of the Indian people, which are playing an ever greater role in international life, in strengthening universal security and peace.

Their trip would also lead to several statements, communiques, and policy proposals being signed by Bulganin, Khrushchev, and Nehru affirming their joint commitment to cultivating sympathetic political and economic relations. In material terms, these promises were upheld, to cite a few examples, through the Soviet Union’s targeted sales of ferrous metals and mining equipment; its support in establishing a steel plant in Bhilai in 1955, and its organization of regular shipping lines between the two countries.

Khrushchev, Bulganin, and Nehru in New Delhi, 1955. Image: Photo Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India.

In addition to formal diplomatic relations between the two countries, Soviet soft power was also central to shaping India’s postcolonial cultural life. From the broadcasting of Soviet radio plays to the export of translated literature ranging from Tolstoy to chemistry textbooks, Soviet soft power was as foundational as — and indeed inextricable from — technological, scientific, and economic collaborations between the two countries. Bulganin and other Soviet officials understood the importance of cultural diplomacy in fostering friendly relations between the Soviet Union and India, proclaiming “there is no need to speak of the significance of this [exchange] and how it facilitates spiritual enrichment.” Of all the sites of Indo-Soviet cultural exchange, cinema was by far the most popular on both sides.

Indian Filmmakers, Soviet Aesthetics

At the Indian Film Festival of 1954, millions of Russians thronged to Moscow theatres to catch a glimpse of the Indian actors, directors, and writers who had descended on the city. Devouring films like Raj Kapoor and K.A. Abbas’ Awara (1951) and Chetan Anand’s Aandhiyan (1952), both threaded with unmistakably socialist undertones, Soviet audiences were enthralled by the Indian film industry. Thirty-seven Indian films were imported and screened in the first post-Stalinist decade, and by the late 1960s, each copy of an imported Indian hit was shown on average 2.5 times more extensively than its Soviet competitors. Soviet audiences were so enamored with these films that negative reviews invited a flurry of distraught letters, and even the occasional death threat, directed to the offending magazine. In a retrospective essay on Bollywood’s impact in the Soviet Union, cinema critic Aleksandr Lipkov recounts that, upon publishing a harsh commentary on Raj Kapoor’s Sangam (1964), he received a message from “someone by the name of Ikhtiandr Zib, [who] promised to slit my throat if I ever fell into his hand.”

Raj Kapoor surrounded by fans in Moscow, 1967. Image: Yoda Press.

Indian film enthusiasts were as excited as their Soviet counterparts to engage with the world of Soviet cinema. Four years before the Moscow festival, Nikolai Cherkasov, one of Stalin’s favorite actors, and Vsevolod Pudovkin, an acclaimed director, landed in India. Invited by the Bombay and Calcutta committees organizing the first Soviet Film Festival in the country, Cherkasov and Pudovkin spent forty days visiting film studios, meeting with directors, cinematographers, and producers including Mrinal Sen and Prithviraj Kapoor, giving presentations, and leading workshops for actors.

The Soviet film delegation came at a time when the Communist Party of India (CPI), after two decades of censorship, arrests, and underground organizing, was allowed unprecedented access to the public sphere. The party’s influence grew rapidly through the various groups in its cultural front — from the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) and the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) to several Indo-Soviet Friendship Societies and Cine-Clubs. Many filmmakers, actors, music directors and others active in the film industry of the 1950s and 1960s were associated with the CPI, either directly or indirectly: director and screenwriter Mrinal Sen was a self-described Marxist; director Ritwik Ghatak, music director and songwriter Salil Chowdhury, and actors Balraj Sahni and Utpal Datt all joined the CPI in their youth; K.A. Abbas and Prithviraj Kapoor, though they never officially joined the CPI, were associated with IPTA throughout their careers. Many of these filmmakers and actors would visit the Soviet Union in September 1954 to attend the Indian Film Festival in Moscow, further solidifying Indo-Soviet artistic connections.

These affiliations with the CPI, IPTA, and the Soviet film industry were reflected in the films and writings of these filmmakers, who transformed and reinvented the aesthetic and political inheritances of Soviet cinema. In his book of essays, Cinema and I, director Ritwik Ghatak cites Sergei Eisenstein, Lev Kuleshov, and Esfir Shub’s cinematic experiments as influences on his work. Ghatak found the darkly galvanizing and “emotionally shattering” work of Soviet wartime documentary filmmakers and “cameramen-soldiers” incredibly compelling, and sought to emulate their approach to film as revolutionary practice in his renowned Partition Trilogy. Ghatak also directed a short documentary entitled Amar Lenin (1970) for the Government of West Bengal, which begins with a dramatic rendering of Lenin’s life in the form of a jatra — a traditional form of folk-theatre popular in rural Bengal — and ends with a rousing rendition of “L’Internationale” in Bengali.

Classical Soviet cinema — especially Kuleshov and Eisenstein’s innovations in formalism and montage theory, which directly applied Marxist dialectical materialism to film editing methods — also resonated in the work of Mrinal Sen, Satyajit Ray, and other proponents of parallel cinema. Sen was especially moved by Eisenstein’s aesthetic sensibility, publishing a 1945 article entitled “Film and the People” that sought to “look at Indian literature and life in the way Eisenstein wrote.” In films ranging from Bhuvan Shome (1969) to Akaler Sandhane (1980), he employed Soviet-style montage to interrogate the relationship between the rural and the urban, the past and the present.

In addition to integrating Soviet techniques and methods into their work, Indian filmmakers, especially those associated with the CPI and IPTA, also embraced a socialist political orientation that was heavily influenced by Soviet discourses on labor, capitalism, and class consciousness. For some directors, this preoccupation took the form of a direct engagement with foundational Soviet texts. Chetan Anand’s widely acclaimed Neecha Nagar (1946), for example, is an adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s groundbreaking play The Lower Depths (1902), which ruminates on Marxist concepts of alienation, social reproduction and false consciousness through an examination of impoverished workers living in a shelter on the banks of the Volga. Anand’s film transposes these themes to the Indian village, where villagers band together to resist the land-grabbing attempts of an avaricious capitalist, always dressed impeccably in a suit and smoking a foreign cigar. At once an allegory of the then-crumbling British Raj — the antagonist is provocatively named “Sarkar” — and a call for collective action, Neecha Nagar became the first Indian film to be recognized at the Cannes Film Festival.

“ Indian filmmakers also invested Soviet-style political messaging with their own subcontinental brand of socialist politics. ”

For other directors, like K.A. Abbas, the flood tide of socialist thought emanating from the Soviet Union provided fertile ground for more subtle, less propagandistic cinematic experiments. Abbas’ enthusiasm for neorealism stemmed from his admiration of Soviet filmmakers, whose work he described as “lyrical, honest, and true” in his 1977 memoir, I Am Not an Island. For Abbas, embodying these qualities necessitated reproducing and reappropriating the working class subject-matter of Soviet films in the Indian context, a task he accomplished through the production of films like Dharti Ke Lal (1946), based on the Bengal famine of 1943, and Jagte Raho (1956), which centers the tribulations of a poor villager who moves to the city in search of a better life, only to be caught up in a complex web of corruption and greed. While selecting leftist themes, alluding to communist theory, and overtly using Soviet texts, Indian filmmakers also invested Soviet-style political messaging with their own subcontinental brand of socialist politics.

Pardesi and the Picturization of Socialist Internationalism

Perhaps nowhere is the rich complexity of this political entanglement made more clear than in Abbas and Pronin’s Pardesi, which traces the real-life voyages of fifteenth-century traveler Afanasy Nikitin from Tver, a small city on the outskirts of Moscow, down the Volga, through Persia and finally to India. Based on his travelog, The Journey Beyond Three Seas, now part of the Russian literary canon, the film is a look at India through the eyes of a welcomed stranger. After outwitting a manipulative Portuguese merchant who betrays him by stealing his coins and puncturing his waterskin — perhaps another allusion to India’s anticolonial struggle — Afanasy, played by Oleg Strizhenov, disembarks in what we presume to be Maharashtra. There, he befriends Sakharam, a folk-singer played by Balraj Sahni, and Champa, a farmer’s daughter played by Nargis, who he miraculously saves from a fatal snakebite. Afanasy and Champa spend the monsoons together and fall in love until he hears of her engagement to a man of her family’s choice. Distraught, Afanasy leaves Champa and resumes his wanderings — punctuated by fleeting encounters with an entrancing court dancer, played by Padmini, and the grand vizier of the Bidar Sultanate, played by Prithviraj Kapoor — before returning home.

“ By fostering genuine understanding between the ordinary people of different nations, as opposed to the elite, Pardesi’s protagonists envision and enact a progressive world-making project. ”

Although set in the fifteenth-century, the film has a working class-centered internationalist message of forging socialist unity — no matter how anachronistic — across national, linguistic, and cultural differences. Afanasy’s open-hearted wanderlust, in contrast to, for example, Miguel’s exploitative capitalist ambition, is framed not as an end in itself, but rather as a means to a more egalitarian world. By fostering genuine understanding between the ordinary people of different nations, as opposed to the elite, Pardesi’s protagonists envision and enact a progressive world-making project.

Let us take Afanasy and Champa, the film’s central pair, as an example. Champa seems to straddle two distinct roles in the film: the first, in line with late and postcolonial depictions of the nation as mother, she appears as the idealized embodiment of Indian life; secondly, perhaps as a nod to Soviet aspirations of gender equality, she is a largely self-sufficient working woman. Afanasy’s attraction to both aspects of her persona is made clear throughout the film, but particularly in the song-dance sequence “Rim Jhim Barse Pani,” in which Champa, along with the other village women, delight in the monsoon. Cutting between shots of Champa ensconced in the branches of a tree waiting for the rains and shots of her working alongside other women, balancing pots of water on their hips, grinding grain, and kneading clay for artisanal pottery, the song celebrates both Champa’s beauty as an extension of the rain-soaked Indian landscape as well as the labor performed by Indian women. Throughout the song, Afanasy is seen sneaking glimpses of Champa, at one point losing his concentration entirely and dropping his tiller while helping her father plow. In valorizing Champa as a signifier of Indian culture and dignified village labor, and by showing Afanasy’s attraction to both, these scenes chart a politics of working class solidarity across borders.

A still from Pardesi: Champa and Afanasy seeking shelter from the rains. Image: IMDB.

In addition to alluding to a working class internationalism and Soviet ideas of gender equality, Pardesi, by invoking Afanasy’s travels as the genesis of contemporary Indo-Soviet relations, legitimizes the Soviet Union’s sovereign claims over Central Asia. Directors Abbas and Pronin, however, were not the first to bring attention to this origin story. Bulganin, in his address to the Indian Parliament on November 21, 1955, proclaimed:

The friendship between our peoples has its source in the distant past. Almost five centuries ago, long before the first European vessels came to the shores of your country, a Russian traveler, Afanasy Nikitin, visited India and wrote a book, outstanding for its time, about the marvelous country in which he spent several years and which he came to love ardently. This was the first “discovery of India” by the Russians.

Here, Bulganin distinguishes between the “European vessels” of the colonizing West (i.e. Britain, Portugal, France, the Dutch etc.) and Afanasy’s “ardent love” for India. Russia, and by extension the Soviet Union, laid claims to an entirely different moral system and origin myth than the West. These same connotations guide the film, which underscores histories of mercantile trade across Eurasian kingdoms, situating Russia as part of the long geographical, historical, and economic continuum of the East. Afanasy, though he has traveled far, is not quite a foreigner. Whereas the West was foreign and extractive, Russia in this rendering was both familiar and friendly.

“As the tone of today’s Indian film industry has turned increasingly towards religious extremism and an insular nationalism, this history offers a window into a bygone aesthetic and political sensibility.”

Thus, by refashioning Soviet concepts of aesthetics, political solidarity, gender equality, and history, Pardesi and other Indian films of the 1950s and 1960s were able to articulate a cosmopolitan, progressive vision. As the tone of today’s Indian film industry has turned increasingly towards religious extremism and an insular nationalism, this history offers a window into a bygone aesthetic and political sensibility. Though it is unlikely that India and Russia will “meet again” as Sakharam and Afanasy hoped, this history invites us to reimagine cinema as a medium for reflecting and producing — not ethno-religious strife or capitalist dreams — but socialist and internationalist solidarities.

Ria Modak is a musician and PhD student at Brown University studying modern South Asian history. Her research explores the intersections of music, nationalism, and borders in late-colonial and postcolonial India.