You Are Not Welcome Here: Race and Hostility in Britain’s Fast Fashion Industry

South Asian garment workers in Leicester are resisting precarity and institutionalised racism in Britain’s “hostile environment” for immigrants.

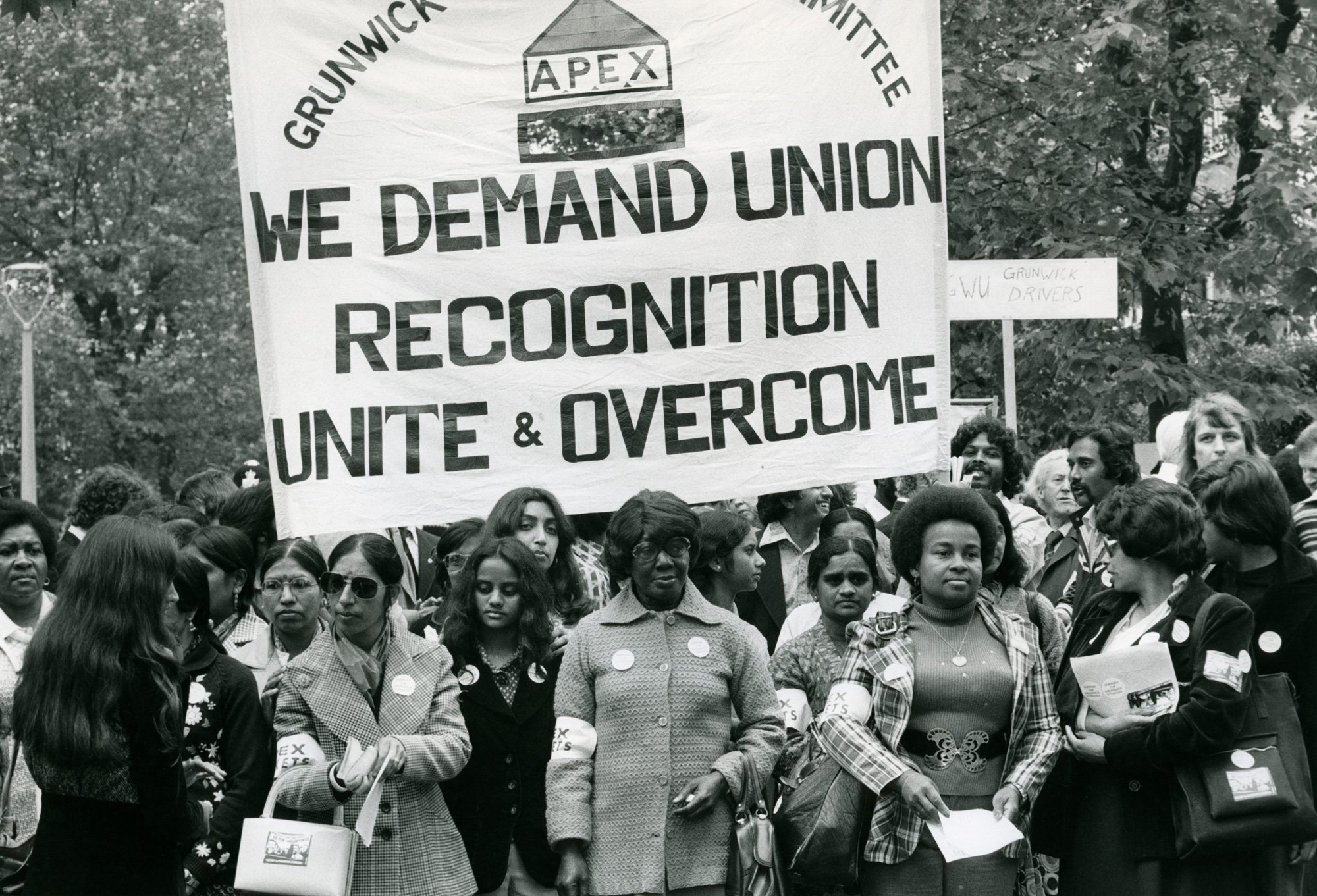

Jayaben Desai, a leader of the Grunwick strike, saluting fellow picketers in 1977. The strike, primarily led by South Asian women, reflected the difficult social and working conditions faced by migrant South Asian workers in the UK. Image: Homer Sykes

The Rana Plaza tragedy happened 10 years after the International Labour Organization (ILO) declared April 28 as World Day for Safety and Health at Work. Yet almost a decade after Rana Plaza, the ILO felt compelled again to declare, “a safe and healthy working environment is a fundamental principle and right at work — the battle for workers’ health and safety is far from over.

This essay focuses on persistent precarity in the working conditions of the largely South Asian workforce in the UK garment hub of Leicester. We reflect on how this precarity is produced and reproduced by an interplay of factors at different scales — global, national, and local. These include a racialised and gendered trade union movement; an institutionalised hostile environment for immigrants; and shifts from collective bargaining to individual labour rights advocacy and from secure employment to rampant outsourcing in a global supply chain. These factors together cement South Asian workers’ dependence on intra-ethnic networks that are both supportive and exploitative.

We consider South Asian workers as those from countries in the Indian subcontinent and their diasporas (e.g. East Africa), including recent first-generation and more established immigrants to the UK. Of the economically active population in England and Wales, 4.5% have Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi backgrounds. More recently, many Indian workers have come to the UK on the skilled worker visa. However, 37% of Indian-origin workers and 53% from Pakistan and other South Asian countries are in occupations categorised as “medium-low skill” or “low skill”. About one-sixth of the undocumented “semi” or “un-skilled” workers in the UK are from India alone. As problematic as this concept and classification of skill is, these official labels are a useful indication of the type of labour South Asian workers are associated with.

Workers at Faiza Fashion in Leicester, UK. Multiple investigations over the past decade have exposed dangerous and oppressive working conditions in the UK garment hub of Leicester. Image: Daily Mail

Behind the Scenes in Leicester’s Fast Fashion Industry

Three years before Rana Plaza, an investigation revealed not only that clothes for popular British brands were being made under unsafe working conditions in Leicester, but also for less than half the UK’s national minimum wage. The sweatshop that drew the most scrutiny in this investigation was housed in the former Imperial Typewriter Works, well regarded for labour rights in its heyday in the 1930s.

Following the Second World War, Leicester, one of the UK’s manufacturing hubs, attracted many immigrants and refugees from the Indian subcontinent and East Africa. Many of these refugees were from the trading class in East Africa and were able to set up their own small businesses fairly quickly. Other immigrants became “low-skilled” workers in businesses such as Imperial Typewriters or the city’s hosiery, shoes, and textile factories. By the 1970s, these industries started to decline though they continued to hire South Asian workers as cheap labour. South Asians with assets used this opportunity to move into manufacturing, initially with refurbished old machinery. By 2007, Leicester became the hub for reinvigorating the UK’s shrinking garment industry in the face of rampant global outsourcing. The revival involved adoption of the fast fashion model, in which “items are produced in small batches, delivered to stores within ten days and … can be reordered, adjusted if needed, and again delivered … without the need to hold large stocks.” The Imperial building now hosted several factories, which not only employed South Asian workers but were often owned and managed by South Asians.

“In 2010, media reports showed trendy clothes being stitched in dilapidated buildings under egregious conditions in Leicester”

In 2010, media reports showed trendy clothes being stitched in dilapidated buildings under egregious conditions in Leicester — dangling wires, blocked fire escapes, flammable textiles stacked in areas near hot machinery, lack of vacation and sick pay, and wages much below the UK minimum wage. In retail warehouses, workers were walking over 10 miles per shift in unventilated buildings. In 2015, an Ethical Trading Initiative research project revealed that the situation remained grim, with workers reporting “health problems, inadequate health and safety standards, verbal abuse, bullying, threats, and humiliation.” Another follow-up in 2017 revealed similar issues, along with the fact that factory units investing in appropriate working conditions and wages were forced to compete against the undercutting of regulation-evading units who received tacit encouragement from brands. Due to multilevel outsourcing, brands claimed to be unaware of the companies producing their garments — the onus of workers’ welfare thus fell through the cracks. It was no one’s responsibility.

In 2022, protestors demonstrated in front of the online retailer Boohoo’s headquarters in Manchester, UK. Multiple protests were organized on Black Friday to draw attention to Boohoo's unfair labour practices subjecting workers to deplorable conditions. Image: Manchesterworld.uk

In 2020, the industry made headlines again when Leicester experienced a spike in COVID-19 infections during pandemic lockdowns. An investigation by Labour Behind the Label (LBL) revealed that with the increase in internet shopping, units supplying the online retailer Boohoo disregarded safe distancing and other precautions, while participating in furlough fraud, wage theft, and modern slavery. The UK government’s labour exploitation watchdog, Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA), responded by setting up Operation Tacit, but there were no significant prosecutions. Factory directors who had been exposed for refusing to pay minimum wages in the 2017 report were still trading in 2021. Unsafe structural conditions still prevailed. There was little induction training due to which workers mostly remained unaware of their rights and health and safety regulations. Moreover, employers often humiliated workers and threatened to sack them or close down if they complained. As Kaenut Issufo, Lead Community Engagement Officer at LBL, explained: “Not much has changed in the last 25 years since my mother was a garment worker”.

Racialised Industry and Anti-immigration Policies

An advert placed in the Uganda Argus (1972) by the Leicester City Council warning South Asian refugees fleeing Uganda against resettling in Leicester. Source: Ned Newitt

In 1972, many South Asians facing expulsion from Uganda and Kenya read a shocking notice in Uganda Argus placed by Leicester City Council. “In your interests,” stated the advert, “you should not come to Leicester.” Similarly, more recent South Asian workers have had to negotiate the UK’s anti-immigration “hostile environment” policies, made explicit in legislation since 2012. State-supported services are scant and insensitive in the neighbourhoods where these workers are likely to live and work. Though English is not spoken or understood by a large majority of workers, these services are often available only in English or must be accessed online, which requires a basic level of literacy. Work visa renewal can be costly and time consuming, further enhancing the precarity of workers paid bare subsistence wages. Those with no recourse to public funds have to pay an annual immigrant health surcharge, which is currently £624.

How does this wider culture of racism in the UK impact interactions between local trade unions and immigrant workers struggling for labour rights in the country? Ever since South Asian workers began arriving in the UK, as laskars and ayahs in the 17th century to factory workers at the height of the industrial period after WWII, their experiences and struggles for labour rights have been shaped by racism, colonialism, imperialism (and casteism emanating from the subcontinent). Immigrant workers are paid lower wages and bonuses, and have fewer upskilling opportunities. They face greater monitoring on the shopfloor, racist abuse, more rigid and poorer work conditions, and comparative less support from trade unions.

In the early years, South Asian workers formed separate organisations, a notable example being the Indian Workers’ Association (IWA). Formed in 1937, the IWA played a major role in labour and anti-racism struggles of the 1960s-1980s: the Rockware Glass factory (1962), Courtaulds Red Scar Mill, Dura Tube & Wire and Woolfe’s Rubber Factory strikes (1965) are significant in the UK’s “Black” labour history. (In this context, the term Black typically includes everyone from a historically colonised context and those who continue to face racism).

“South Asian workers engaged with mainstream unions, demanding recognition of their disputes and representation on the shop floor. The unions’ bureaucracies, however, with their racist undertones, betrayed immigrant strikers at critical points”

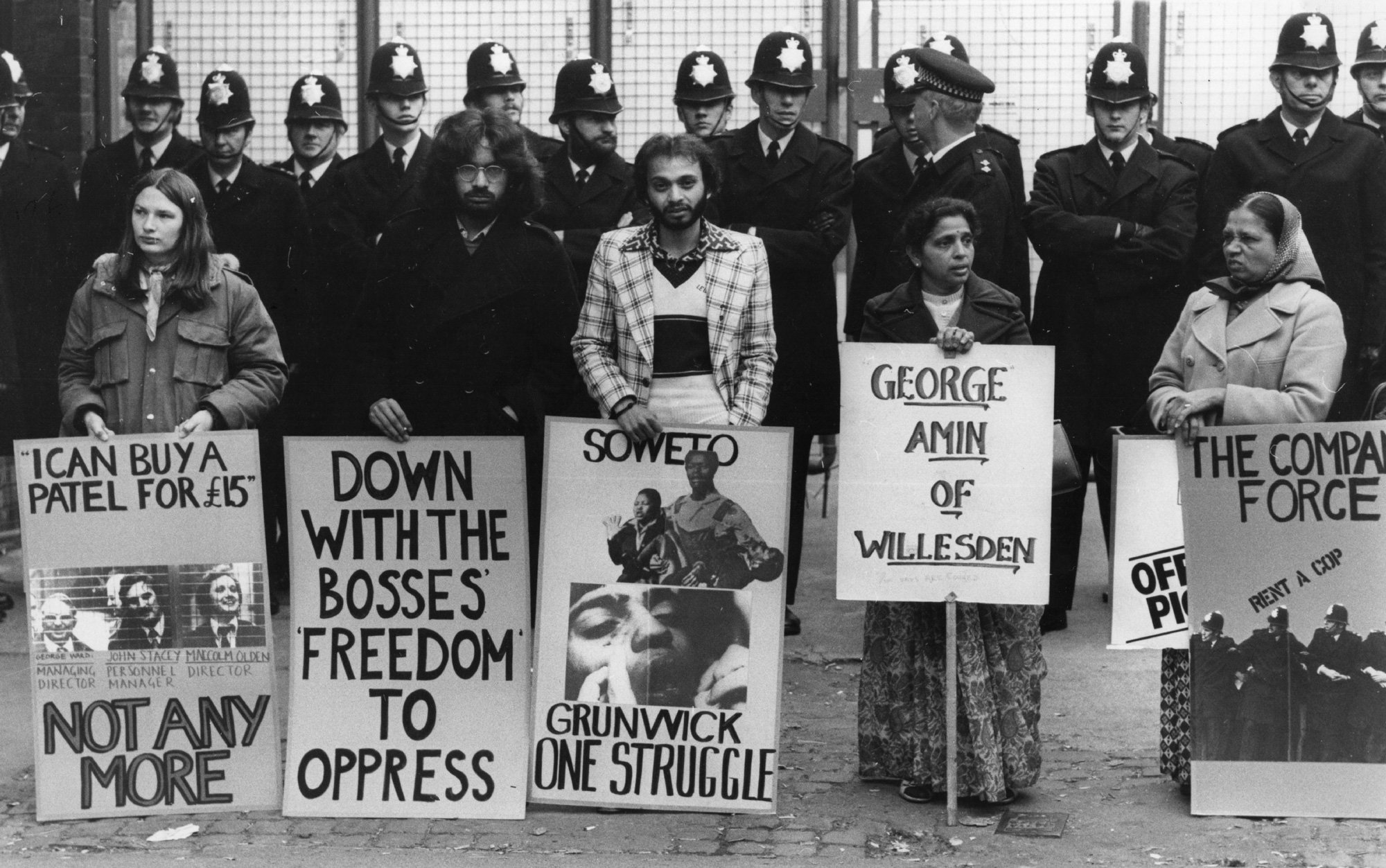

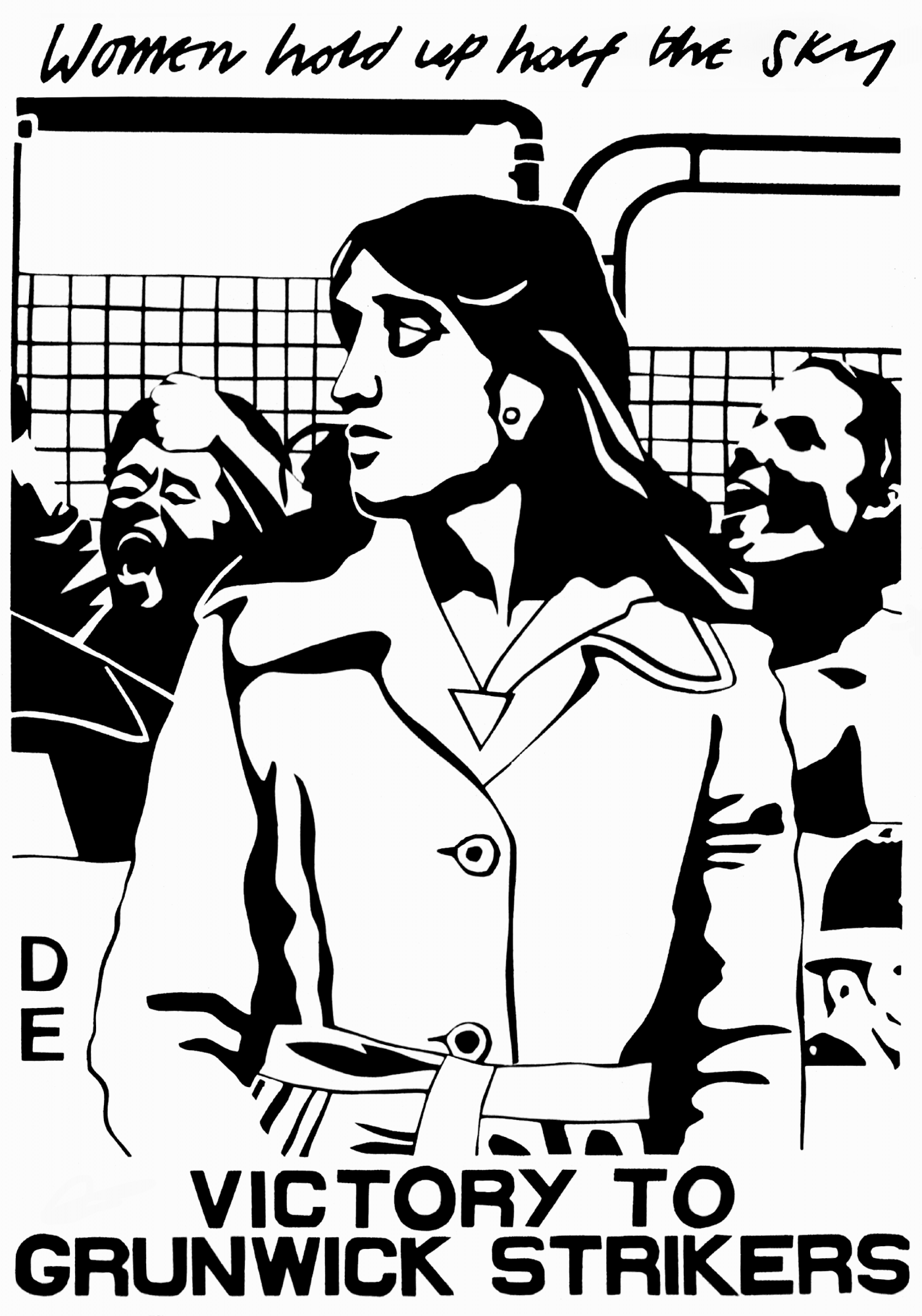

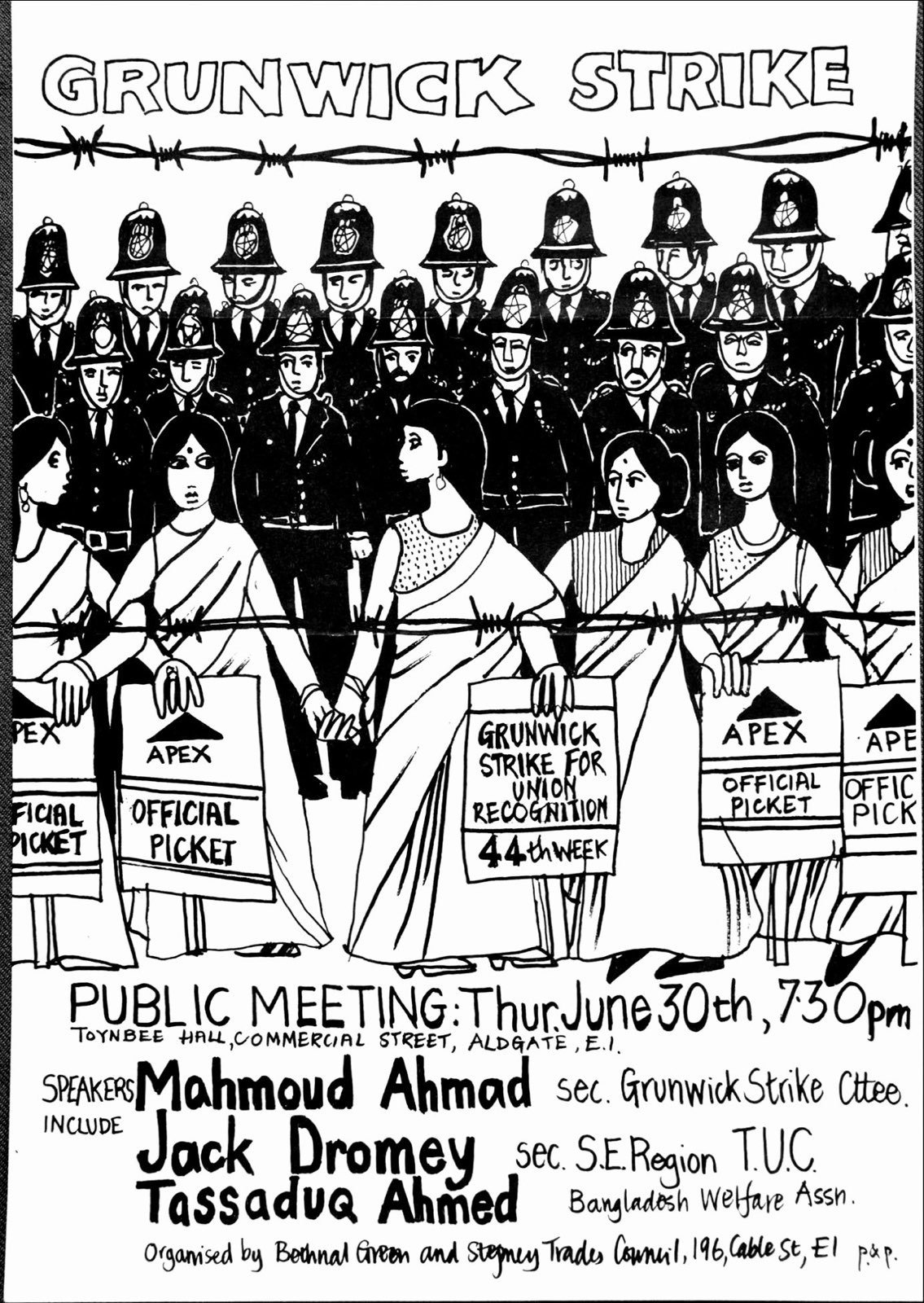

These predominantly male workers’ strikes were succeeded by further disputes – among which Imperial Typewriters (1974), Grunwick (1976–78), Burnsall (1992), and Gate Gourmet at Heathrow (2005) became emblematic. These strikes were led by South Asian women workers who were often hired for their “docility,” but who displayed a “surprising” spirit on the picket line. They set up independent strike committees, and directly liaised with the wider labour movement, civil society, and the public to mobilise mass picketing and solidarity boycotts. These included postal workers, miners, dockers and others in Grunwick, and baggage handlers and ground crew at Heathrow. The Grunwick strikers countered domestic patriarchal resistance to stand up for themselves by uniting their roles as mothers and housewives with their roles as income contributors.

Images and posters from the Grunwick strike, UK (1976-78). The strike was mainly led by migrant female South Asian workers who had fled persecution in Uganda and were working under deplorable conditions in Grunwick’s factories and also facing significant racial hostilities. Images: British Library (Courtesy of Evening Standard/Getty); The Poster Collective; People’s History Museum (Dan Jones).

Throughout, South Asian workers engaged with mainstream unions, as both longstanding or new members, demanding recognition of their disputes and representation on the shop floor. The unions’ bureaucracies, however, with their racist undertones, betrayed the immigrant strikers at critical points. One such instance was in the Burnsall strike:

Trade unions would often say it was too much trouble to organise [South Asian workers]. Language barriers and the lack of unity in the workplace – due to isolating line work – were obstacles unions were afraid to tackle … Some union bureaucrats feared, if they supported immigrant strikers too much they’d fragment workers elsewhere. The union refused to produce a leaflet and offered no strategy for how to win.

The politics of solidarity of these trade unions was underpinned by stereotypical understandings of immigrant workers rooted in structural racism. The unions were mediating not as representatives of Black workers but as ‘“lieutenants” of capital, more concerned with people “learning how things are done in a civilised society” than mobilising sections of the class for political change.

Ultimately, the Grunwick strike was defeated and presaged wider defeats for working class struggles in the 1980s, including the powerful but unsuccessful national miners’ strike in 1984-85. Both strikes were defeated, in large part, owing to the role played by union bureaucracies in discouraging solidarity action. If postal workers, for example, had continued to boycott Grunwick’s mail order post, that strike may have ended differently. More widespread solidarity action in support of the miners might have done the same. On different scales, both strikes involved mass mobilisation, mass picketing, militancy, and confrontations with the state. The Grunwick strike portended the violence that would be meted out to the miners: widespread arrests, police violence, and mobilization of every aspect of the state as a co-ordinated force to crush the strike.

“South Asian women workers in the hosiery factories of Leicester continued being marginalised by largely White male-led unions. The workers, in turn, did not trust the unions to take up their issues effectively.”

As the employers’ lobbies and the state armed up to defeat workers, the labour movement’s strategies were weakening and becoming less effective, rather than gaining strength from the victories of the 1950s-70s. First, aided by anti-strike laws, union leaders worked to undermine and distance themselves from concepts of class-wide struggle towards more carefully controlled, individually siloed disputes. Come the 1980s, unsurprisingly, South Asian women workers in the hosiery factories of Leicester continued to be marginalised by largely White male-led unions. The workers, in turn, did not trust the unions to take up their issues effectively. The so-called “lack of interest in unionising” among South Asian workers is in fact a consequence of historically being sidelined by trade unions under racist assumptions and stereotyping.

Second, over the past three decades, under Conservative and New Labour governments, the liberal rights-based regulatory framework underpinning the UK's labour market has contracted the space for “enterprise-level industrial relations and worker representation” via trade unions. Rather, this framework favours “evidence” of good practice in the form of “selective monitoring” by planned inspections and “worker-driven complaints.” Unions thus began focusing on advocacy on a case-by-case basis (via employment tribunals), working in “partnership” with employers, rather than through collective bargaining. For factory workers in Leicester, this route has never been easy in light of the financial expense of taking a case to court. This requires support from a union or advocacy organisation, and appointing a solicitor to deal with the legalese in addition to interpreters in the court hearing. The fear of the factory being closed down with many job losses also lies heavily on the person making a case in a tribunal.

Between 2010 and 2022, 18–20% of Asian or Asian British employees were trade union members, compared with 24–30% Black or Black British, 23–27% White British, 17–24% Mixed ethnicity, and 11–18% of Chinese workers. These patterns of union membership, we argue, must be understood in the historical and structural context of racism in the UK (including and especially its trade union movement), along with the persistence of precarity and exclusion in the industry.

Corporate Responsibility and the Supply Chain Model

The “revitalisation” of Leicester’s garment industry in the early 2000s happened as part of the wider neoliberal globalisation of Western manufacturing industries. The garment industry’s new supply-chain model stands on several levels of subcontracting and a workforce distributed across multiple nodes. This meant that units in Leicester went from 250 to fewer than 10 workers. Contractors across the supply chain often further sub-contract to unregistered units using informal payroll systems to deliver high volumes quickly on tight budgets. Labour inspectors can find it “hard to keep track” of these units, which “are often registered and wound up at astonishing speed.” As a GLAA official explained: “Inspections of unsatisfactory premises would merely lead to a plethora of new ‘start-up’ businesses happy to evade inspection.” In intra-ethnic workspaces, owners/managers may play the system through “coercive practices” operating with “a different set of social and cultural factors.” It is important to be mindful that institutional factors enable such exploitation in the first place.

After the investigative report in 2010, brands had suggested reforms like regular audits and spot surprise checks. However, as the UK Trades Union Congress (TUC) notes, the rate of official inspections remains under the ILO benchmark due to insufficient numbers of inspectors. In 2022, the UK Low Pay Commission also demanded a review of labour regulations and changes in complaints procedures because workers in low wage sectors do not have confidence in them. Moreover, due to their vulnerable right-to-work status, gender, race, class, or caste identities, or precarious socioeconomic situations, they are less likely to register complaints. Workers also worry that if they complain, their employer will move their production to countries where they can avail cheaper labour and side step UK’s more stringent labour regulations. With the closure of units after the exposés, there are in fact fewer complaints in light of fewer jobs and more competition between workers.

The above developments encapsulate how market-driven and anti-immigrant state policies foster precarity. The supply chain model allows brands to distance themselves from taking any responsibility for violations against workers on the ground, while outsourcing, casualization, scarcity, and state hostility further discipline workers into taking up precarious work. In Leicester, as in other parts of the UK, the neglect of immigrant workers by mainstream trade unions means that workers must only rely on intra-ethnic networks for support and work.

Intra-ethnic Workplaces: Sites of Support and Vulnerability

Dan Jones’ Look back at Grunwick, is a celebration of the Grunwick strikers. His work related to the strike is a tribute to the power of multi-racial coalition building and labour activism. Image: British Library (Dan Jones)

Although Leicester’s garment industry workers come from various ethnic backgrounds, the majority are South Asian. Many women are from the west coast of India (adjoining the state of Gujarat) who still experience the deprivations of historical caste-based occupational, socio-economic, and educational marginalisation. English is their second language and they may not have reading skills in any language. However, they often have machine skills, and are comfortable in jobs that do not require (Western) dress code or interactions with unrelated men.

Employers are frequently second or third-generation South Asians. As a result, South Asian socio-cultural beliefs and practices often shape employer-employee relations. As mentioned earlier, the paucity of local state welfare services, coupled with language constraints and generalised state hostility towards immigrants and welfare claimants, drives people to community networks for support and job opportunities. Especially after the pandemic and the LBL exposé led to many factory closures, new immigrants from South Asia are “accommodated” through networks of shared ethnic ties, which often engenders dependency and indebtedness. Even though the workers are “free” to leave whenever they want, cultural norms (e.g. around gratitude), gendered practices, and limited English language and Western work experience, do not allow the women to easily leave exploitative workplaces.

Finally, the prior lived experiences of immigrant workers may also impact how they understand their employment experience in the UK. A comparison of the women at Grunwick, Gate Gourmet (Heathrow), and the garment industry in Leicester is informative. Many Grunwick women were first-time strikers — urbane, English-speaking Gujarati Hindus in their 20s or 30s, who were “respectable” middle class workers or homemakers in East Africa with no experience of unionising. Their initial foray into the strike was resisted by their families. The Gate Gourmet women, in contrast, were older immigrants from largely rural farming communities of Punjab. They had a history of participating in successful strikes in the UK (e.g. Hillingdon and Lufthansa Skychef in the 1990s). However, they came from landed farming families and often had servants do their own “menial” work in Punjab. Therefore, in both cases, the women experienced “downward” mobility in the workplace. This significantly fuelled their frustration with the material discriminations that triggered them to stage a walkout.

South Asian women in the garment industry today come from more impoverished backgrounds. Their primary goal is supporting their household expenses. There is also a level of comfort in work for which they may already possess necessary skills and are not required to travel far afield from home. They also may wish to avoid confrontation in employment relations that are interconnected with wider community relations. This does not mean they do not want good working conditions — however, instead of putting the onus of the struggle against exploitation primarily on their shoulders, it is important that solutions start from a focus on the structural conditions which undergird labour exploitation in Leicester and undermine workers’ power or opportunities for collective bargaining.

Here, a nuance missing in available research is whether caste-based discrimination is also present in these workplaces. We would argue that because it is well established that caste exploitation travels from South Asia to its diasporas, including UK workplaces, future research with South Asian workers should also examine whether the disregard for workers’ health and safety is also inflected by ethnic and casteist undervaluing of the lives of those from historically oppressed caste and other marginalised backgrounds.

It is important to acknowledge that South Asian workplaces also have contradictions that cut across class or professional distinctions. Suppliers may be at the receiving end of humiliation in their own relations with large brands. Brands may cancel orders suddenly, move production to cheaper sites and so on, keeping suppliers on tenterhooks. In this context, the LBL exposé was significant precisely because it challenged actors across the supply chain, holding not just suppliers but also big brands who are responsible for creating healthy and safe working conditions in factories.

The Way Out

The Rana Plaza tragedy highlighted the need for government agencies and garment brands to take responsibility for ensuring transparency and accountability, healthy and safe work conditions, and workers’ rights. Some UK-based brands have signed the International Accord on Health and Safety that is based on the post-Rana Plaza Bangladesh Accord. How are the brands that outsource to Leicester doing?

The most urgent need of the workers in Leicester is the revival of its garment industry, though with significant reform. Exposés of exploitation should not mean that brands take the easy way out and simply contract suppliers in another location. This is not helpful for workers as conditions of precarity are enhanced when work opportunities shrink, as noted above. Organizations like LBL are instead campaigning for brands to manufacture a certain fixed percentage of products in the UK. Nevertheless, the UK requires humane immigration policies that ensure there are supportive measures in place for immigrants to settle in and find work without feeling indebted to employers from their own community. For instance, there should be accessible support for developing English skills quickly. Both the state and the brands are also responsible for ensuring a healthy level of manufacturing jobs in the country, while fostering a work environment and labour policy that facilitates collective bargaining so that workers can act against exploitation without the fear of losing their job.

When the exploitation of Leicester’s workers during the pandemic became public, the UK Trades Union Congress (TUC) admitted that unions need to step up their community organising approach to ensure they remain “at the heart of a process to stamp out malpractice” and exploitation in a labour market with well-entrenched gig/contract employment relations.

The TUC, LBL, GMB, and Unite unions, along with city council and the local community advocacy centre (Highfields Centre), have set up the Apparel and General Merchandise Public Private Partnership (AGM-PPP). It “aims to put worker voice at the core of the industry and bind brands and unions together to drive up standards.” Through Workplace Support Agreements (WSAs), brands and suppliers allow workplace “access for the union and a commitment from the union to represent individual and collective issues despite little or no membership.” For workplace access, the Fashion-workers Advice Bureau Leicester (FAB-L) outreach initiative has been set up at the Highfields Centre. However, after the diffusion of initial enthusiasm, factories have continued to resist union engagement. As of today, around 15 workers have become union members. To further facilitate participation, unions need to step up their efforts.

“While almost all UK unions have a Black workers’ section today, the question is whether they are impacting the racist framework within which unions operate.”

Another gap that ought to be fixed is the under-representation of ethnic minorities in trade union leadership. While almost all UK unions have a Black workers’ section today, the question is whether they are impacting the racist framework within which unions operate. Emerging struggles in the last decade, like the contract and gig workers’ struggles, have often been led by new multi-ethnic and more militant unions (such as the Independent Workers of Great Britain). Their origin lies in fighting the rejection or poor treatment of racialised workers by mainstream unions. Similar to the South Asian women-led strikes of the past, they use a mix of established and informal rank-and-file unionising strategies by directly taking on traditional employers and clients. They have also been proactive in providing English language lessons, like FAB-L in Leicester.

Ultimately, the achievements and setbacks of Leicester’s garment workers’ struggles point to the need for unions and workers to build sustained solidarity over a long period, rather than coalescing only around a short-term issue or moment. The UK labour movement needs transformation and expansion in all sectors.

Unions need to be “rooted in the workplace” via empowered local branches and campaign explicitly to remove all legal restrictions on unionising and strike action. They also need to ensure linguistic accessibility and inclusion to aid the participation of grassroots immigrant workers. Unions need to fight all disputes with the aim of concrete gains (or concrete prevention of losses), not negotiations as ends in themselves, in which workers’ terms and conditions can be easily traded away.

India Labour Solidarity (ILS) also advocates for inclusion of the Ambedkar Principles in labour regulations. While these principles were developed by the International Dalit Solidarity Network for addressing caste discrimination in the private sector, they can inform inclusion of a social justice approach into employment regulatory frameworks more broadly.

Lotika Singha is a social activist and writer based in the UK, and a member of India Labour Solidarity (UK)

Sacha Ismail is a campaigner, writer and trade union activist in London, UK, and a member of India Labour Solidarity (UK)

India Labour Solidarity (@IndLabSol) promotes solidarity between workers and their trade union and labour movements in the UK, and India and South Asia more broadly. We thank other members of the ILS collective for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of the article.

We are also very grateful to Kaenut Issufo, Lead Community Engagement Officer, Labour Behind the Label, and to Fashion-workers Advice Bureau Leicester at Highfields Centre, Leicester for sharing their insights into the labour-force and conditions of work in the local garment industry.